The MATATAG Curriculum, introduced by the Philippine Department of Education (DepEd) for the 2024–2025 school year, seeks to strengthen the K-12 education system. It prioritizes making lessons more relevant, improving service delivery, supporting teachers, and promoting student well-being.

Key assessments in the country identified significant challenges, emphasizing the need for curriculum reform. Reports from the World Bank and international evaluations such as PISA indicated that while Filipino students demonstrated strong reading skills, their performance in math and science remained weak. Similar trends were observed in other assessments, including TIMSS and SEA-PLM. Both national and international standardized test results show that student performance has remained unchanged (Schleicher, 2018; Mullis et al., 2020; UNICEF & SEAMEO, 2020).

These findings raise concerns about how students develop essential skills, prompting calls for curriculum adjustments that align with global standards. The competencies measured in these assessments should be embedded in classroom instruction to ensure students acquire the knowledge and abilities needed to succeed in an increasingly competitive world.

As I reviewed the MATATAG Curriculum, I couldn’t help but wonder if its development had been influenced by design thinking. Its emphasis on student-centered learning and readiness for both employment and civic life reflects key traits of this methodology.

This eJournal will examine the MATATAG Curriculum through the perspective of design thinking, analyzing its core elements to determine whether its framework incorporates principles from this problem-solving methodology.

Before moving further, let’s first define design thinking.

The Design Thinking Process

Design thinking goes beyond a step-by-step process. It fosters creativity and problem-solving through a flexible and open-ended approach that encourages exploration and adaptation. It provides tools and strategies to uncover solutions, but the actual outcome can vary depending on the specific needs and context of the learners. For these reasons, design thinking becomes a powerful ally in instructional design.

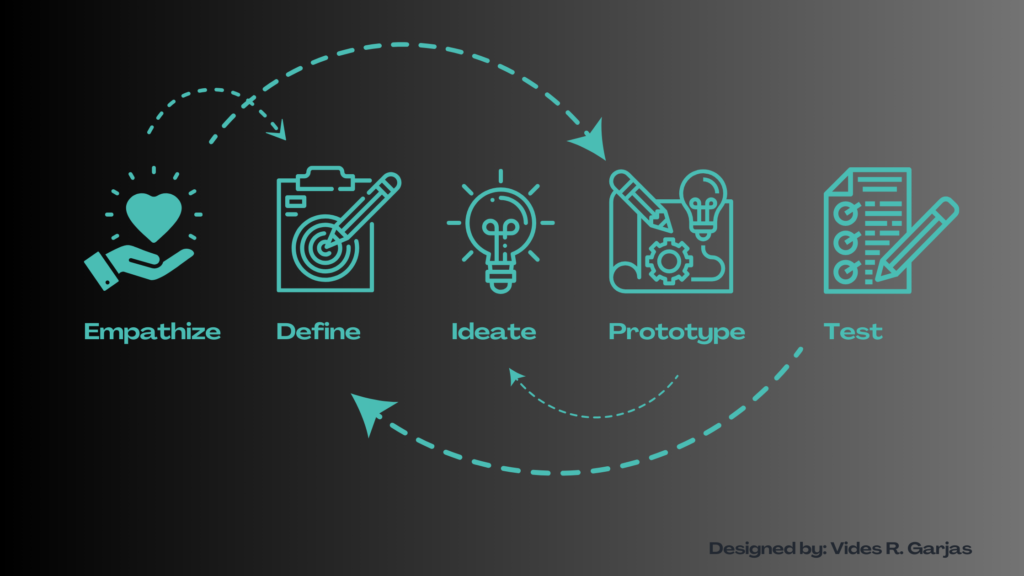

The Design Thinking Process is broken down into five stages: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test. Each stage serves a unique purpose in creating learning experiences. What are they? Let’s find out.

Photo adapted from: Interaction Design Foundation 5 Stages of Design Thinking Process

Stages of Design Thinking

Empathize: Understanding Learner Needs

Empathy is the heart of design thinking. It’s about putting ourselves in others’ shoes to truly understand their needs, challenges, and experiences. Understanding the learners’ needs is the first and most crucial step in the Design Thinking Process. When we ask, “Who am I working for? What is their problem?” we’re really trying to see things from the learners’ perspective. In the context of the MATATAG Curriculum, empathy plays a crucial role in shaping a curriculum by listening to the voices of teachers, students, and parents. The developers of the MATATAG Curriculum aimed to address the real issues that students face in the classroom.

Before rolling out the MATATAG Curriculum, educators and developers gathered feedback from teachers, students, and parents to understand the challenges of the previous K-12 curriculum. Teachers struggled to cover all the required competencies and felt overwhelmed by extra paperwork that cut into their teaching time. Students often felt stressed and disengaged due to the heavy workload, while parents noticed gaps in their children’s education.

The emphasis on empathy ensured that the MATATAG Curriculum was built with the genuine needs of learners in mind, creating a more supportive and effective educational environment.

Define: Framing the Problem

In the “Define” stage of the Design Thinking Process, we take the insights gained from empathizing with our learners and translate them into a clear, actionable problem statement. This step is all about answering the question, “What are the users’ needs?” and making sure we’re asking the right questions to get to the heart of the issue. Asking the right question is critical because it frames the direction of our solution.

For the MATATAG Curriculum, this phase was crucial in pinpointing the main issues that educators and learners faced.

Based on the responses gathered during the empathize stage, one of the biggest challenges identified is content overload. Teachers struggled to cover all the material in the curriculum, leaving little time for in-depth exploration of important topics. This often resulted in students feeling overwhelmed and unable to fully grasp essential concepts. Another challenge was ensuring that the curriculum content aligned with the developmental stages of the students. For instance, some younger students found certain lessons too advanced for their age, making it difficult for them to keep up.

This stage is crucial for building authentic solutions because it allows us to focus on what matters by defining the problem accurately to create solutions that are aligned with both educational goals and learner expectations.

Ideate: Generating Creative Solutions

In the “Ideate” stage of the Design Thinking Process, the goal is to generate as many creative solutions as possible. The mindset here is that no idea is a bad idea—every thought has the potential to spark something valuable. We open the door to innovative and unexpected solutions that might not have been considered otherwise by embracing a maximum of ideation and welcoming different perspectives. It’s like casting a wide net and considering all possibilities.

In the context of the MATATAG Curriculum, ideation played a crucial role in developing innovative approaches to overcome challenges like content overload and the need for better alignment with students’ developmental stages.

During the ideation process, educators and curriculum developers came together to brainstorm creative solutions. One idea that emerged was to streamline the curriculum by reducing the number of learning competencies, allowing teachers to focus on core concepts without overwhelming students. Another innovative idea was to integrate peace competencies and inclusive education programs directly into the curriculum, making it more relevant to students’ lives and promoting a more inclusive learning environment. As these ideas took shape, the team refined them through ongoing collaboration with teachers, school administrators, and other stakeholders. For example, they discussed how to implement a more flexible teaching schedule that would allow teachers to spend more time on challenging topics to ensure that students fully understand the material. This collaborative approach not only strengthened the ideas but also ensured that they were practical and aligned with the realities of the classroom.

Prototype: Developing Practical Solutions

In the “Prototype” stage of the Design Thinking Process, the goal is to develop practical solutions that bring ideas to life in a tangible way. This stage involves creating interactions between the different elements of design, allowing us to see how various components work together and where adjustments might be needed. Prototyping is about making ideas concrete so that we can test them and gather feedback before fully committing to a final solution.

The prototyping phase in design thinking focuses on creating early versions of solutions to test and refine them before full implementation. In the context of the MATATAG Curriculum, this phase involved developing low-fidelity prototypes to address the curriculum’s key challenges. These prototypes served as practical models for testing new approaches and gathering feedback.

For instance, the curriculum developers designed streamlined lesson plans that prioritize essential skills such as reading literacy and numeracy. This approach enables students to engage with concepts more thoroughly without feeling overwhelmed, aligning with the MATATAG curriculum’s focus on reducing the number of learning areas from seven to five. The new learning areas for the Grade 1 classroom—Language, Reading and Literacy, and Makabansa—have been intentionally developed to enhance literacy and numeracy rather than merely combining existing content. The curriculum developer also designed pilot versions of age-appropriate project-based learning activities for Grades 4 and 7 that encouraged them to apply their skills in real-world scenarios. These prototypes are currently being tested in classrooms, where teachers and students provide feedback on their effectiveness.

Prototyping has allowed curriculum developers to quickly identify what works and what needs improvement. If a lesson plan doesn’t resonate with students or a project-based activity proves too complex, developers can make adjustments and test the revised version again. This iterative process ensures that the final instructional materials are practical and aligned with the MATATAG Curriculum’s goals of fostering well-rounded, job-ready citizens.

Test: Refining Solutions for Real-world Application

In the “Test” stage of the Design Thinking Process, the focus shifts to refining solutions for real-world applications. This is where the rubber meets the road, and we determine whether our ideas are practical and effective or if they need to be rethought or even abandoned if they don’t meet expectations.

Testing is crucial because it ensures that the instructional solutions are not just theoretically sound but also practical and ready for implementation. The goal is to have a polished, effective instructional solution that has been refined through real-world application and is ready for broader implementation.

In the context of the MATATAG Curriculum, this phase involves piloting the newly developed educational materials in actual classrooms to evaluate their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement. The curriculum developers launched Phase I to Kindergarten and Grades 1, 4, and 7 levels.

In line with the introduction of new learning areas into a Grade 1 classroom, the educators will observe and gather feedback on how students interact with the material. Teachers will also hold focus groups with students and parents to discuss their experiences and gather insights into what aspects of the lesson plan are challenging.

Based on the feedback, the curriculum developers make iterative revisions to the prototypes, which will likely continue into the next school year. If a particular lesson plan is too difficult for students to grasp or doesn’t align well with their developmental stage, they adjust the content to better fit the learners’ needs. This process of testing and refining ensures that the final instructional materials are not only effective but also closely aligned with the goals of the MATATAG Curriculum—producing competent, job-ready citizens who are well-prepared for the challenges of the 21st century.

To wrap it up, looking at the MATATAG Curriculum through design thinking shows that it takes a smart and caring approach to changing education in the Philippines. The people who developed this curriculum put empathy first. They really listened to what students, teachers, and parents needed.

They tackled key challenges step by step: first by defining the problems, then brainstorming creative ideas, creating practical models, and testing them out. This shows they are serious about making education reform.

As they roll out the first versions of this curriculum, it’s clear that design thinking has shaped it in a big way. The MATATAG Curriculum not only meets the current needs of everyone involved but also sets the stage for a stronger, future-ready generation. This is to hope that the curriculum is an ongoing journey towards an education system that truly supports its learners and prepares them for the challenges of the 21st century.

Final Thoughts: Practical Change, Powered by Design Thinking

The MATATAG Curriculum reflects more than a shift in content. It embodies a resurgent commitment to rethinking how education meets the realities of today. Through its design and development process, it avoided the trappings of a top-down despot model and convened real stakeholders to co-create meaningful change.

As someone entering the field of instructional design, I plan to create flexible content that adapts to diverse learners. My goal is to provide educators with options that match different speeds and styles, backed by interactive case studies and real-world scenarios. Feedback will remain an essential guidepost, not a nuisance to be brushed aside.

Design thinking will continue to guide how I approach instructional challenges. It is neither a panacea nor a salve for every problem, but it does offer a clear framework to produce smart, relevant, and workable solutions for learners who deserve more than guesswork and tommyrot.

References

Dam, R. F. (2023). The 5 stages in the design thinking process. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/5-stages-in-the-design-thinking-process

Dam, R. F., & Siang, T. Y. (2021). What is design thinking and why is it so popular? The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/what-is-design-thinking-and-why-is-it-so-popular

Department of Education. (2023). General shaping paper on MATATAG curriculum. https://www.deped.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/GENERAL-SHAPING-PAPER-2023.pdf

Department of Education. (2023). MATATAG curriculum. https://www.deped.gov.ph/matatag-curriculum/