Systems thinking involves recognizing how different parts of a system are interconnected and understanding how these interactions affect outcomes. Focusing only on one part without considering the whole often leads to incomplete solutions (Kim, 1999).

Think of any system—a machine, a classroom, or a company—as a collection of parts working together. These parts depend on each other to form a cohesive whole that serves a purpose. Without these connections, you don’t have a system—just random pieces. It’s like a bookshelf and a book: alone, each has a limited function, but together, they create a useful purpose—a library where books are organized and accessible.

Context awareness, on the other hand, involves recognizing the environment in which a system operates, both internally (like team dynamics and company culture) and externally (such as market trends and resources). Without this awareness, diagnosing or solving problems accurately becomes nearly impossible. It’s like trying to fix a machine without considering external factors—maybe the machine is too hot, or perhaps the operators lack proper training. Context contributes to the system’s needs just as much as its parts.

Together, systems thinking and context awareness reveal hidden connections and help address issues rather than just surface-level symptoms.

Systems Thinking Tools in Action

Causal Loop Diagram (CLD)

A Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) visually maps out the relationships between different variables in a system, helping to identify and understand the feedback loops that influence behavior over time (Sterman, 2000).

Let me show you how a Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) works, using an example that many of us might relate to.

During my time working the graveyard shift in the BPO industry, I encountered many challenges, including fatigue. As a newbie, I struggled with the city’s chaotic rush, waking up late in the evening while everyone else was wrapping up their day. The transition into this schedule was rough, I had to get used to commuting when public transport options were limited and trying to stay awake during a shift when my body felt like it should be sleeping. It made those first few months feel like I was constantly out of sync with the world. At first, I thought the cause of my constant fatigue and occasional late arrivals was just bad time management. I tried to plan better, set alarms, and leave earlier for work.

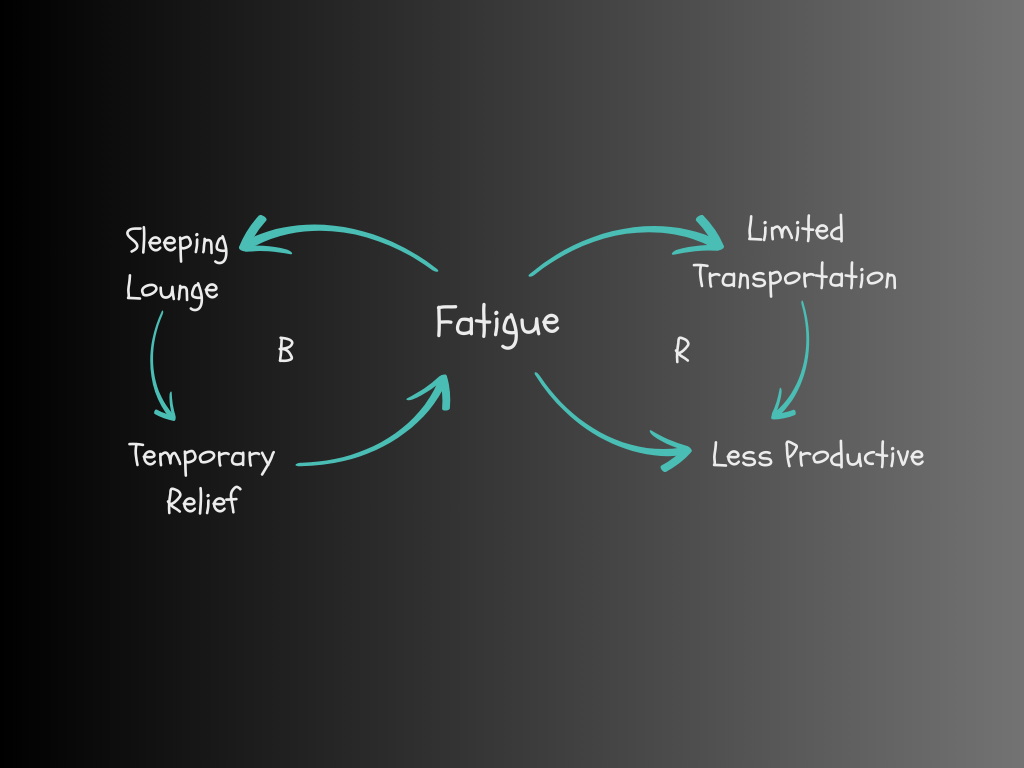

figure 1: Simple Casual Loop Diagram (Adapted from kim 2000) How to Boost productivity while working for a graveyard shift

In the diagram, the Reinforcing Loop is on the right side, involving “Fatigue,” “Limited Transportation,” and “Less Productive.” This loop represents a cycle that worsens over time: limited transportation options lead to fatigue, which then reduces productivity, ultimately feeding back into increased fatigue. This creates a reinforcing process where each factor amplifies the other, making the situation progressively worse.

On the left side, the Balancing Loop involves “Sleeping Lounge,” “Temporary Relief,” and “Fatigue.” Here, the sleeping lounge provides temporary relief to counteract fatigue. This loop seeks to restore some balance by reducing fatigue temporarily, limiting the ongoing impact of the reinforcing loop.

It’s good to think that something as simple as the sleeping lounge offered by the company might seem like just a perk. But now that I think about it, that lounge did more than just provide a place to rest. It cut down on the stress of traveling back and forth, especially late at night. After a shift, instead of battling traffic in a busy city or worrying about how to get home, we could just crash in the lounge and save time and energy for the next workday.

Iceberg Model

Have you ever felt like you’re always reacting to the same kinds of problems, wondering if there’s a way to see the hidden forces driving them? Recently, I’ve been working on constant revision requests from clients, and I started to ask questions if I did something wrong in the process. Or—maybe they’re just indecisive, right? When I read about the mental models in system thinking and came across the Iceberg Model.

The Iceberg Model separates reality into three levels: events, patterns, and systemic structures (Kim 2000). On the surface, events are those daily occurrences we notice and respond to—a missed deadline, a recurring conflict, a product issue. But are these events just random? The Iceberg Model suggests that beneath these events are patterns, like repeated behaviors we see in people or processes. We often hear the phrase “it’s a pattern of behavior” when someone struggles to break a habit. This repetition isn’t just by chance; it points to something more ingrained.

Going down, the model shows systemic structures—those unseen frameworks and norms that contribute to these recurring patterns. Structures like organizational culture, policies, or processes drive the patterns and the surface events. Focusing on all three levels, we reposition from merely reacting to problems to understanding their origins. Here’s how I approach the model using my experience:

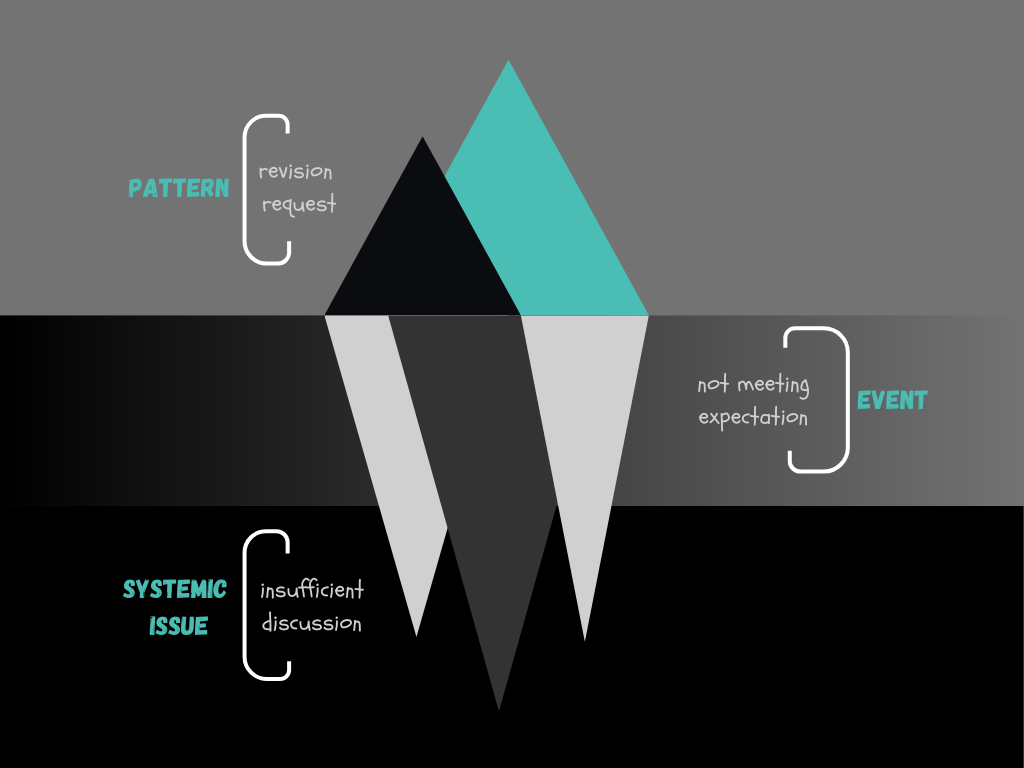

figure 2: Iceberg Model (Adapted from Kim 2000) Why There’s a constant revision from Client’s Requests

Starting at the top, we have the event level. Here, the visible event is not meeting expectations. This represents the immediate, noticeable outcome—like a client feeling unsatisfied or a project not aligning with the expected result. At this level, it’s easy to see that there’s a problem, but it doesn’t tell us why the issue keeps happening.

In the middle, we get to the pattern level, where we see revision requests. These requests happen repeatedly over time, showing a recurring trend or behavior. In this case, the pattern reveals that each project ends up needing additional work, which may suggest a broader communication issue. Patterns like these indicate that this isn’t a one-time event, but rather part of an ongoing cycle.

At the base of the iceberg lies the systemic issue: insufficient discussion. This is the root cause, the underlying factor driving both the visible events and the recurring patterns. Here, the model suggests that a lack of clear, detailed conversations upfront may be causing misalignment and leading to unmet expectations. When communication is lacking from the start, misunderstandings or vague expectations are bound to arise later, resulting in the pattern of frequent revision requests.

In this case, I realized I had been taking on too many clients without fully discussing expectations upfront. This led to misunderstandings, which showed up later as revision requests. The structure below the pattern showed that my client’s communication process needed improvement, and at the mental model level, I hadn’t been giving communication the priority it deserved. Once I addressed these issues, the revisions became much less frequent. It suggests that the visible “event” (the revision requests) is just the tip of the iceberg. Beneath that event lies a pattern, and in this case, that pattern is miscommunication.

Bringing Systems Thinking and Context Awareness into Future Problem-Solving

Systems thinking and context awareness now form the basis of how I address challenges in instructional design. I assess how systems behave—not in fragments, but as interconnected frameworks shaped by environments, expectations, and feedback loops. This approach matters in settings like higher education, where design choices influence institutional strategy. Instructional designers perform audits, analyze feedback, and collaborate with key stakeholders to identify specific areas of friction. They implement changes that persist because they respond to structure, not symptoms (Bond et al., 2023).

Small adjustments—targeted support for instructors or using learner input can produce measurable results. Yet innovation must be introduced with discernment. Instructional designers are tasked with refining processes, not disrupting them arbitrarily. Testing, observing consequences, and applying revisions iteratively prevents instability from taking root.

Both systems thinking and context awareness revealed how each environment contains embedded forces that must be accounted for. These frameworks prompted me to analyze what lies beneath surface-level issues and equipped me to anticipate challenges more strategically. Engaging all relevant actors—students, teachers, administrators, and professional teams—enables instructional designs that serve actual needs rather than superficial demands.

I intend to integrate this perspective across all stages of my work. It strengthens analysis, supports foresight, and contributes to instructional outcomes that endure beyond implementation.

References

Bond, A., Lockee, B., & Blevins, S. (2023, October 31). Instructional Designers as Institutional Change

Agents. Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2023/10/instructional-designers-as-institutional

change-agents

Kim, D. H. (1999). Introduction to Systems Thinking. Pegasus Communications.

https://thesystemsthinker.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Introduction-to-Systems-Thinking

IMS013Epk.pdf

Kim, D. H. (2000). Systems thinking tools. Pegasus Communications, Inc.

https://thesystemsthinker.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Systems-Thinking-Tools-TRST01E.pdf

Lyon, A. (2017, 22 February). Systems Theory of Organizations [Video file].

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1L1c-EKOY-w